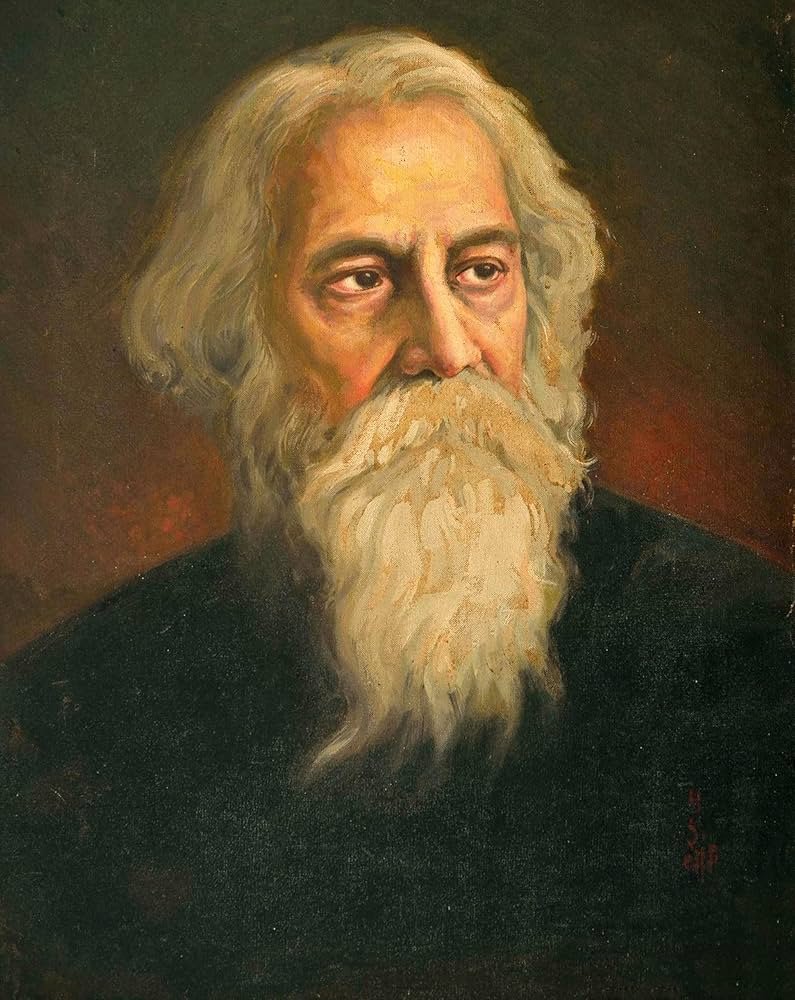

A journey through the life and legacy of Rabindranath Tagore.

The Cradle of My Being: Birthplace and Early Years

I was born in the heart of Kolkata, in the ancestral home of my family, the Tagores, on the 7th of May, 1861. The air of Jorasanko Thakur Bari was thick with the scent of history, art, and an abiding intellectual spirit. This was a household where music, poetry, and philosophical discourses flowed like the morning sun. My father, Debendranath Tagore, a towering figure of the Bengal Renaissance, and my mother, Sarada Devi, a woman of quiet strength and deep devotion, were the guiding stars of my early life.

The growth of a child in this atmosphere was like being nurtured in a garden with various flowers blooming. The first world of a sprawling mansion with its yards and gardens, with their rooms full of artwork and literature, left an indelible mark on my young mind: music rehearsals, learned discussions, and quiet contemplation by my father. The bustling life in the streets of Kolkata, its busy markets, and the serene banks of the Ganges all wove together to shape my perceptions. It was a time of awakening, where the seeds of curiosity and creativity were sown.

A Tapestry of Learning: Education and Intellectual Growth

Speaking mildly, my formal education was quite a restless affair. I attended some of the best schools in Kolkata, including the famous St. Xavier’s School, but found the rigidity of structure and rote learning stifling to my imaginative spirit. For me, the joy of discovery was often cut short by the demands of examinations and set curricula. After all, as the saying goes, it is indeed “The world is my teacher,” and the world outside became my true university.

My father, recognising the unconventional spirit in me, took me on a tour of Northern India when I was barely fourteen years old. This tour was not merely a physical journey but an awakening of the soul. A travel through the Himalayas, a visit to ancient temples, and a look at the diversified landscape and people of India marked my young consciousness indelibly. It was during this time that I really started delving deep into the ocean called Indian literature, philosophy, and spirituality. The Vedas, the Upanishads, and the epics such as the Mahabharata and the Ramayana were my constant companions.

My education was thus a continuous process of self-discovery and engagement with the world. I read voraciously, absorbing knowledge from diverse sources-from the poets of ancient Greece to the mystics of Persia, from the scientific discoveries of the West to the profound spiritual traditions of the East. I learned languages, not just to decipher texts, but to understand the nuances of thought and emotion that each language carried. This eclectic approach to learning allowed me to weave a rich tapestry of knowledge, in which different threads of wisdom intertwined to form my unique perspective.

A Haven for the Soul: Facilities Built by My Efforts

It was this search for an integrated and imaginative education that would bring harmony in the mind, body, and spirit, which compelled me to create institutions which would aspire for these conceptions, among which the most conspicuous is Visva-Bharati University at Santiniketan.

Visva-Bharati was not conceived as yet another educational institution; it had to be the living embodiment of the spirit of universalism, a place where the best of India’s cultural heritage would meet with the finest of global knowledge. The very name, Visva-Bharati, signifies “the world united with India.” I envisioned a place where learning would be an intimate communion with nature, where students would study under the shade of trees, and where the boundaries between the teacher and the taught would be blurred by mutual respect and intellectual curiosity.

The early experiments with education began in a very lowly setting in the village Santiniketan in Bengal, which I had come into possession of from my father. I thereby started an ashram school where children, under the open sky in the midst of trees, learned through observation, interaction, and creative expression. There would be emphasis on the child-centred approach, nurturing the inborn curiosity and allowing them to explore their innate talents.

Visva-Bharati was to grow into a full-fledged university that would eventually become the hub of learning in Indian art, music, dance, literature, philosophy, and science. It attracted students and scholars from all over the country and the world and helped create an atmosphere of cross-cultural interaction and intellectual debate. Even the architecture at Santiniketan, the open-air classrooms, the unpretentious yet graceful buildings blending with the surroundings, was meant to evoke a feeling of harmony and peace. And I believed this was an environment in which the human spirit could best flower.

Besides Visva-Bharati, I had engaged myself with some other undertakings that looked forward to social reforms and the development of villages. Experiences in Shantiniketan made me believe in rural reconstruction and self-sufficiency. I tried to establish model villages and cottage industries, believing that true progress lay in empowering the common people and reviving their traditional skills.

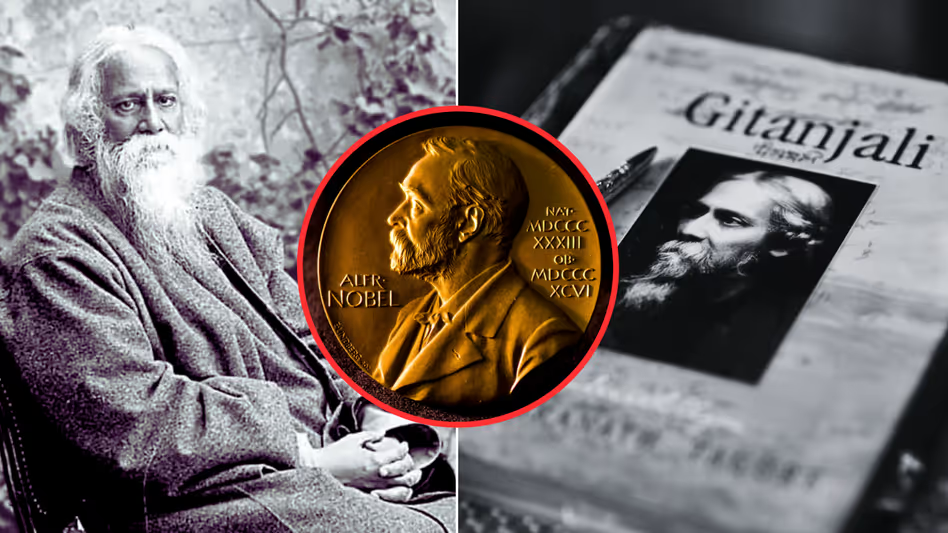

The Golden Feather in My Cap: The Nobel Prize

The year 1913 brought a profound moment of recognition from the distant shores of Sweden. I was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for my collection of poems, Gitanjali. Far more than a personal triumph, it was, to my mind, a recognition on the world stage of the spiritual depth and aesthetic beauty of Indian literature.

Gitanjali means “song offerings,” and this was a compilation of my spiritual, devotional poems. I had done the translations in English of some of them as their author, a deeply laborious task of giving rebirth to my words in English. The reception of Gitanjali in the West was overwhelming. It resonated with many who were seeking solace, spiritual connection, and a deeper understanding of life. The prize was testimony to the universal appeal of my verses speaking of nature, love, devotion, and the eternal quest for the divine.

This prestige connected with the Nobel Prize left me with a burden of increased responsibility. The Nobel Prize brought along with it a spotlight, and I used this platform to advocate for the richness of Indian culture and the need for greater understanding and respect between East and West. Literature and art, I believed, have the capacity to overcome divisions and build empathy, and the Nobel Prize gave further strength to my voice. It was a moment of great pride, not for me alone but for India too.

A Song of Freedom: Contribution to the Freedom Struggle

I joined Freedom for India not through direct political activism in the general sense but through the power of my voice, my philosophy, and my unflinching spirit of patriotism. I held a belief that true freedom was not mere political independence; rather, it was liberation of the mind and spirit from every form of oppression, whether extrinsic or intrinsic.

During the British rule, I witnessed the deep injustices and the stifling of the Indian spirit. Though I never joined any political party nor participated in violent protests, my writings, my songs, and my pronouncements before the public were a constant source of inspiration and a soft yet firm challenge to the colonial power.

One of the strongest moments of my involvement was the protest against the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919. The brutal violence of this act, where innocent Indian civilians were mercilessly gunned down by British troops, hurt my heart very much. In reaction to this horrific event, I gave up the title “Sir,” which had been ordained upon me by the British government. This was a strong statement of my dissent and my refusal to accept any honour from a regime which could perpetrate such atrocities. It was a declaration that my conscience was worth more than any title or decoration.

My songs, such as “Amar Shonar Bangla” (My Golden Bengal), which later became the national anthem of Bangladesh, and “Jana Gana Mana,” the national anthem of India, were more than melodies but anthems for national identity, unity, and the yearning for self-determination. They evoked a sense of pride and belonging, and the evocation of a collective consciousness that was, in essence, a freedom movement.

I was also an ardent advocate of the Swadeshi movement to boycott foreign goods and nurture Indian industries. So, self-supporting and indigenous renaissance through arts and industries were recurring themes in most of my writings, believing that economic freedom formed a base for political freedom.

Above all, my philosophy of “humanism” and my insistence on universalism made Indians rise above narrow confines and view themselves as a part of the world entity while taking pride in their distinctive culture. I was an apostle of an educational system that promoted a questioning, inquiring spirit among people. To me, an awakened mass was the cornerstone of a free nation. My involvement was, in fact, a spiritual-cultural awakening to make the Indian spirit free from all bondage.

A Human Heartbeat in My Words

As I look back on my life, I am reminded of what it means to be human: to love, to sorrow, to joy, to wonder, and to connect. My writings, I trust, have always borne this human pulse. They have sought to probe the depths of the human soul, the beauty of the natural world, and the eternal verities which link us all.

The whole of my life has been continuous learning, continuous creating, and continuous striving to comprehend the mystery of existence. From the crowded lanes of Kolkata to the silent hugs of Santiniketan, from the depths of spiritual Gitanjali to the echo of the call for freedom, all experiences have integrated into my being.

My deepest hope is that my work may continue to inspire, comfort, and awaken the beauty and divinity within each one of us. After all, it is not the standing ovations or the achievements that matter most, but rather the love we share, the understanding we cultivate, and the light we bring into this world.

Dhanyawad for letting me share these humble reflections with you. May your own journey be filled with creativity, compassion, and the boundless spirit of discovery.